| News |

Monday, January 18, 2016, 1:51AM

Over the MLK Holiday Weekend, the '07A Vipers played in their first tournament as a team. They traveled to snowy NH to play a weekend set against the East Coast Wizards, the Seacoast Spartans and Top Gun in the 2d Annual Granite State Ice Fest held at The Rinks at Exeter facility in Exeter, NH.

The weekend started with an early morning start against the East Coast Wizards. One of the team's only 3 losses of the season came at the hands of the East Coast Wizards early in the year. Having played the Wizards twice and scrimmaged against them in 2 Turbo+ games (fast-moving, fun-filled, music-blaring 4-on-4 games at Holland), the team knew what to expect--a well-coached team of fast skaters, tenacious forecheckers and relentless backcheckers--from their friends the Wizards. And that's what they got--but its also what they gave! The team came out flying, playing great positional and disciplined hockey resulting in a convincing 3-0 win. The Wizards offense kept coming, but great defense, solid backchecking and, above all, phenomenal goal-tending kept the threat at bay.

Following the Wizards game, the team had a 3 hour layover that was filled with team bonding over pizza and bowling. Definitely a great time for everyone and a great opportunity for the players to become closer to their teammates.

The team returned to the rink to meet a new opponent from the BHL, the Seacoast Spartans. The team came out a bit flat and fell victim to a number of power play goals (two on 5-on-3 situations) by the Spartans to fall to a 5-2 deficit entering the third--those five goals are the most that any team has scored on the '07A Vipers all season. It was not looking good, but, to a player, the team regained its composure, committed to winning races to the puck, no more penalties, no more giveaways, no more goals against and backchecking. With impressive passing, speed and positional play, the team stunned the Spartans and battled back to a 5-5 tie at the end of regulation! Not having been in such a deficit position all season, the team proved to itself that it had the ability and the character to come from behind! Notwithstanding the team did not ultimately win, the emotion of the moment filled them with excitement and pride in their accomplishment. It was a sight to see and experience!

After having Sunday morning to sleep in, the 07 Vipers came to the rink with the top seed in the tournament. Building on the commitments made in the comeback against the Spartans, the team played Top Gun in dominating fashion. Crisp passing, heads up play and great backchecking proved too much forTop Gun to handle and guided the team to an 8-1 win. With the Wizards having defeated Top Gun the day before (with their friends, the 07 Vipers, in the stands chanting "LET'S GO WIZARDS") and the Spartans earlier in the day, the Championship game was set between two well-matched teams who have come to respect one another and to expect a hard-played game from each. The teams and the fans were not disappointed.

As has become custom between these two teams, the players wished each other "good luck" before entering their respective locker rooms in a tremendous display of sportsmanship. While respected friends, there's no mercy on the ice for either team. Both teams came out hard, playing fast and disciplined two-way hockey. With a renewed commitment to the system and trust in their teammates, together with the exceptional goaltending they have come to expect, the 07 Vipers entered the final minutes of the game with a 3-1 lead. The Wizards made it interesting with a goal with 45 seconds to go, having pulled their goalie and added the extra attacker. The Wizards did not give up. They pushed their way into the offensive zone as the clock wound down, but disciplined defensive positioning and a timely save sealed the deal for the 07 Vipers!! Champions in their first tournament!!

The game was capped by a medal ceremony in which the team respected and congratulated its opponents and friends, the Wizards, in a manner that befits the values of the Viper organization. A great weekend for the 07 Vipers and the Viper organization!!

Tuesday, December 15, 2015, 4:21PM

Part of the the Greater Boston Vipers hockey program includes having the players get involved in a charity event. This year, the 06AAA team chose to collect donations for soldiers based on a list provided by www.supportoursoldiers.com . Team manager, Trish Murphy, did an unbelievable job organizing and scheduling the event. After asking family, friends and neighbors to contribute, the players gathered an incredible amount of supplies and would present them after their game on Saturday 12/12/15. There was one special request from a soldier in Saudi Arabia working with disabled children, doing equestrian therapy. Small toys was the request and the team did not disappoint. Two boxes of them will be going to this cause. Speaking of boxes, a special thank you went out to Saugus Military Families for supplying them and shipping the goods to the Middle East. Inside each of the 25 boxes went a personal note from players and friends with well wishes and tons of questions asking about military life. To make the event even more special, two soldiers, Lance Corporal First Class Nicholas Russo of the United States Marines and Petty Officer Second Class Sergio Palacios of the United States Navy visited the rink to collect the donations. They not only witnessed a strong showing by the team against the Providence Junior Friars but enjoyed a family skate after the game. The team was very thankful to the both of them for taking time out of their busy schedules to help with such a great cause. With the win over Providence and an awesome collection of supplies heading to our soldiers, the team, family and friends could not have asked for a better day!

Wednesday, December 9, 2015, 4:51PM

Our thoughts and prayers go out to the Rosato family of Danvers. On Sunday, JJ Rosato an 8yr old who played for Top Gun passed away in his sleep. In this small interconnected hockey world, we all have a lot of with connections to JJ.

"A friend, a teammate, and a child gone much too soon. Thinking of JJ and peace for the Rosato family"

Friends of the Rosato Family have established a GoFundMe page at: https://www.gofundme.com/5qdnvxsc

His Funeral Mass will be celebrated on Saturday, December 12, 2015 at 11 a.m. in Saint Mary of Annunciation Church, 24 Conant St., Danvers. Burial will follow in Annunciation Cemetery, Danvers. Relatives and friends are invited. Visiting hours are Friday from 4 to 8 p.m. in C.R. Lyons & Sons Funeral Directors, 28 Elm St., Danvers Square.

Monday, December 7, 2015, 8:33PM

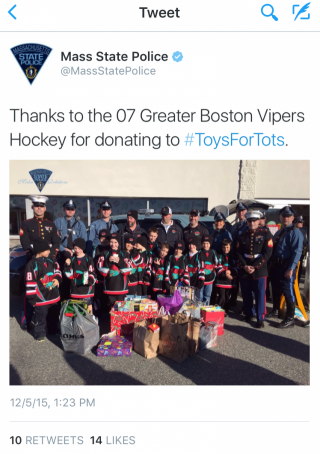

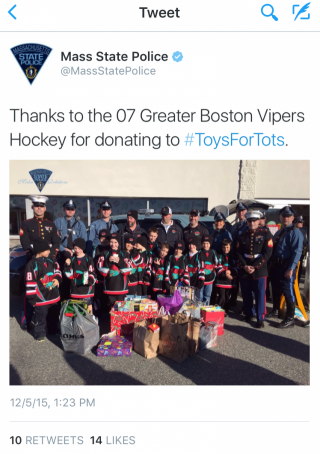

The 07A Vipers created a festive

atmosphere with holiday music, hot

cocoa, snacks, family and friends and

scored a huge goal at the Massachusetts

State Police "FILL THE CRUISER" event

held at the Woburn Toys R Us on

Saturday, December 5th. Each player

was asked to solicit at least 5 toys for

children less fortunate than them. The

team came up big and donated well over

100 toys!! They also encouraged others

entering the store to do the same with

tremendous success. The Mass State

Police recognized the 07's efforts with

postings on their Facebook page and the

Tweet pictured above.

"The Coaching staff was extremely proud

of the team's commitment to and follow

through on the event," said Coach

Cush. "The compliments from the

Marines and the Troopers about their

generosity and their polite and respectful

behavior was testament to the players’,

their parents’ and the Viper organization’s

commitment to being good citizens who

care about their community.”

Monday, November 30, 2015, 1:19PM

With extreme determination and grit, the 06 Greater Boston Vipers put together an incredibly strong November, going 6-1-0 in their division, 6-1-1 overall. Building on their solid foundation of fast skating, battling hard for the puck and playing a team game, they've become a formidable opponent in the EMHL.

No team goes far without a strong goalie between the pipes and Mike Murphy more than fits the bill. As one of the most athletic players on the team, “Murf†makes some acrobatic saves look easy. The team will need his focus and skill to be at a high level as they head into the meat of their schedule.

�

Standing in front of Murf are some of the steadiest defensemen in the league. With a long reach, Jimmy Driscoll provides a steady force on the blue line at right D, never giving up on a play, always sending the puck away from harm. Playing left D, Cam Sullivan tracks down the opponent's speedy forwards, makes the transition game happen and adds explosive offense when the opportunity presents itself. The Norton brothers have split time on both D and forward. Will Norton shows off his strong skating and deft hands while playing both positions. Always in the mix, making plays and setting the tone, he is an integral part of every shift. When the team needs grit and and a physical boost, Aidan Norton is there to provide one. Never afraid to go into the corners and do the dirty work, Aidan has done a stellar job, whether on the point or digging for a tough goal in front of the other teams' net. The other two players who have taken a regular shift on D are Ryan MacEachern and Nick Brandano. Ryan joined the team at the end of the summer and what an addition he has become. When the term “utility player†is used, Ryan's name comes to mind. Whether asked to play D, wing or center, MacEachern does the job with a “yes coachâ€, “I'll take care of it†attitude. The coaching staff can't ask for more than that! Nick's game begins with a strong blue line presence. Holding the opposing team deep in their zone is the key to success. Pinching in, holding the boards, forceful dump ins, are all part of Brandano's game. He contributes the same effort on forward too!

�

While a good goaltender and strong defense certainly are the back bone of a team, wins don't happen without scoring goals. The offense on this Vipers team can only be described as dangerous. Using a strong forecheck, they attack with a purpose and constant pressure. The forwards group has been on fire lately and it all starts with aggressive play deep in the offensive zone. Two players on this Vipers team are perfect examples of aggressive, tough on the puck wingers, Steve Migliero and Zac Benedetto. Benedetto takes after his policeman dad and lays down the law in the corners, using his strong body to out-muscle and extract the puck from anyone in his way. Migliero, one of the biggest and most physical players on the team, plays a similar game. Digging and doing the dirty work along the boards is not always fun but Steve seems to enjoy the battles with a smile. Dillon Reilly, a skilled winger and center, uses his speed and puck carrying ability wisely. Reilly will drive into the offensive zone with a goal in mind and either pop one in or crash the net for loose pucks. Another speedy wing, Braedon Flanagan has been steadily increasing his point total. With a high tempo motor, Flanagan is relied upon to carry the puck through the neutral zone and does a superb job of it, firing the puck on net for goals or generating rebounds. When talking about rebound goals, Brendan Heffron's name comes to mind. Playing wing, he seems to have a knack for being in the right spot at the right time. Hockey sense is a big part of his game and it guides him into the perfect position for one timer goals on a consistent basis. Heffron also plays a feisty game along the boards and in the corners.

Coming into this season, no one knew what to expect from this team. Now that they are deep into it, an identity is forming, one of hard work and and a never give up attitude. The team is becoming one, pulling for each other, sticking up for each other, eating together, practicing hard together, winning and losing games together. No player on this team can do it alone and they have come to realize this. Heading into December after an incredible November, they'll need to continue this all for one mentality to carry them through the upcoming grind. Keep an eye on this 06 Vipers team. They will be fun to watch!

Tuesday, November 24, 2015, 8:43PM

� � This holiday season the 06 AAA Viper team will be sending care packages to Soldiers who are deployed overseas. � Our hope is that each player will ask family, friends and neighbors to donate a total of 5-10 of the items on the attached list.� We will also be sending pictures and cards made by the players along with a team picture.

�

�� � Please have all donations into Trish or Mike by December 10th.� You can bring donations to any practice or game starting Saturday, November 28th.

�

�� � A few Soldiers will tentatively pick up our donation at the Family Skate on December 12th.� If we do not end up having the family skate, the Soldiers will come to one of our games to pick up the packages.

�

�� � Coach Sully will explain all of this to the boys on Wednesday (11/25) at practice.� He will also hand out envelopes with the donation requests and paper for the boys to draw �“Thank You†cards or posters to the Troops. � Thanksgiving is a great time for the boys to talk to family and friends about donating to this special cause. �

�

Please hand the pictures/cards to Trish by December 10th as well!

� �

Contact Trish with any questions!

Tuesday, November 24, 2015, 4:14PM

The '07AAA Venom will be Proudly Supporting the Massachusetts State Police in their Annual "FILL THE CRUISER" Event for at the Woburn Toys R Us on Saturday, December 5th @ 1 p.m.

An important part of the Vipers mission is to develop fine young men and women both

on and off the ice. As part of that mission, each team is required to participate in at least

one charitable event during the season. This year our team will be supporting the Toys

for Tots charity by participating in the Massachusetts State Police "Fill the Cruiser"

event. As many of you know, our own Carly Constantine (mother of #18 Riley) is a

proud member of the Massachusetts State Police, so we thought it fitting to support her

in her efforts with Toys for Tots this year, making it a family event. To that end, we are

asking that each player solicit donations of five (5) new, unwrapped, non-violent toys for

ages newborn to 14 from family members, friends or neighbors to donate at the Fill the

Cruiser Event to be held at the Woburn Toys R Us (366 Cambridge St.) on December

5th. We will meet at 1pm in the parking lot to present our gifts as a team and take a

team picture. Asking them to gather 5 presents will give our players the opportunity to

think about the reason for Toys for Tots (see the Toys for Tots objectives below) and

give them the opportunity to make a difference through their actions. We'll also have

some hot chocolate and treats (nut-free of course) for the kids and the Mounted Police

Unit will be there to introduce the kids to the horses and take pictures. As Carly always

says, "Horses make everything much cooler."

Please let me or Carly know if you have any questions.

Leslie

Mission, Goal, and Objectives of the Toys for Tots Program

Mission: The mission of the Toys for Tots Program is to collect new, unwrapped toys

and distribute those as Christmas gifts to less fortunate children in the community where

they are collected.

Goal: The primary goal of Toys for Tots is to deliver, through a new toy at Christmas, a

message of hope to less fortunate youth that will assist them in becoming responsible,

productive patriotic citizens.

Objectives: The objectives of Toys for Tots are to help less fortunate children

throughout the United States experience the joy of Christmas; to play an active role in

the development of one of our nation's most valuable resources -- our children; to unite

all members of local communities in a common cause each year during the annual

collection and distribution campaign; and to contribute to better communities in the

future.

Monday, November 16, 2015, 2:00PM

The 6th annual Vipers Parent Appreciation Night at Kowloon Restaurant is scheduled for: Thursday, November 19th, 2015 @ 7:00pm.

Dinner and Entertainment will be provided by the Vipers. Cash Bar. Dinner will be served at 7pm which will be followed by a Comedy Show. This is an adult-only event.

All Vipers on-ice events have been rescheduled so that everyone can all have a night away from the rinks to relax and enjoy ourselves. This event is always a lot of fun for the parents each year.

RAFFLE/AUCTION ITEMS:

Items will be 100% tax deductible. If you have:

Please email: vipers@vipersicehockey.com with more specifics.

We are working with a 501(c)3 Charity again this year with proceeds benefiting the Patrick Gill Scholarship that was started last year. As most of you know, Patrick was an overwhelming personality on the 97Vipers and his memory will continue to help Vipers families for years to come.

Thank you.

Monday, November 9, 2015, 2:29PM

The online Apparel Store is open until 12:00 noon today.

To ensure all items arrive in time for Christmas, all sales are final as of today at noon.

This will be the final apparel order for this season.

Here is the direct link: www.vipersicehockey.com/store

All sales are final and the Vipers will not be ordering extra stock.

If you have any questions, please email: apparel@vipersicehockey.com

Tuesday, October 20, 2015, 8:15PM

Welcome to the all new Vipers website. The site has been completely redesigned with a new sharp look.

Some new items that will be coming soon:

- The Venom Club

- Alumni Page

- 2016-17 Tryout Page

If you haven't already, connect with the Schedule iCal on your mobile devices so that you are always up-to-date with your child's schedule.

If you notice any links that are not working, please notify: vipers@vipersicehockey.com

|

|

|